Historic Water and Land Use

Learn More

Other Websites

To best understand the patterns we discern in the landscape, it is helpful to know something of the history of a place.

Explore this page:

History of the Land at Rock Creek Park

Pre-Historic: Native Americans and Fire

Nomadic Native Americans occupied the present-day area of the park at various times before the coming of European settlers. Eastern Algonquian-speaking people established semi-permanent settlements in the Rock Creek area.1 Evidence suggests they burned the forests to create open areas to facilitate travel, prepare land for agriculture, and improve the habitat and food sources for the animals they hunted. This probably resulted in areas of open forests dominated by trees such as chestnut oak and other oaks able to survive repeated fires.

Dry ridgetop areas of the park today are still largely dominated by Chestnut Oak / Mountain Laurel Forest and the Mixed Oak / Heath Forest, both of which contain many fire-adapted species. This is just as we would expect after repeated fires of natural and human causes in the region, because once started, fire tends to move upslope and run along ridgelines, weeding out fire-sensitive plant species.2

Pre-Civil War: Sparse Settlement

Steep slopes with rock outcrops made agricultural development in the Rock Creek valley unfeasible.

Steep slopes with rock outcrops made agricultural development in the Rock Creek valley unfeasible.

Photographer: Ery LargayIn 1662, early European settlers were given land grants of up to 6,000 acres in the Rock Creek region. The Rock Creek valley was only sparsely settled by the tenants or owners of these large tracts of land. Small areas were cleared for agriculture or timber-harvest. Large-scale development was prevented by the lack of adequate transportation across the deep Rock Creek valley. Poor soils, steep-sided slopes and ravines, and rocky terrain protected many of Rock Creek’s forests from being cleared for the lucrative commercial tobacco production.3

In the early 1800s, the Peirce family, prominent landowners of the time, built plant nurseries near Peirce Mill and Klingle Mansion (just north of the present-day National Zoological Park) to supply street trees and ornamental plants for the nation’s new capital city.4 Clues to the former existence of these nurseries and the orchards that were common along Rock Creek’s floodplains can be seen in the park today; some of these plants, both native and non-native to the eastern United States, have naturalized in adjacent Rock Creek forests. Ecobit: Maple Tree Mystery

Ruins of a historic mill on Rock Creek (in foreground).

Ruins of a historic mill on Rock Creek (in foreground).

Photographer: Gary FlemingThe Peirce family also built a gristmill on Rock Creek, which operated from the 1820s to 1897. It was one of at least eight mills along Rock Creek in the Washington, D.C. area in the 1800s, most of which shut down before 1900. A rocky dam several hundred yards upstream of Peirce mill directed water into a trench called a millrace, where the rushing water turned the mill’s waterwheel. A decorative dam was added at Peirce Mill in 1903, after the mill had shut down. Dams like this prevented spawning fish from swimming upstream in the spring. Today, a fish ladder allows fish to swim past this dam—see Rock Creek Fish Passage in Current Water and Land Use and watch a video about Rock Creek Fish Ladder.

The Civil War: Clearing Land and Building Forts, Trenches, Roads

The land around Rock Creek changed radically during the Civil War. Military Road—the first major east-west thoroughfare across the expanse of Rock Creek valley—was created for military transport.5 Essentially the entire area of the park north of Military Road was cleared of trees, and the land was burned to maintain clear sightlines between forts, and unobstructed views of approaching troops.6

Fort Stevens as it was during the Civil War. It is located just east of Rock Creek, part of today's Fort Circle Parks.

Fort Stevens as it was during the Civil War. It is located just east of Rock Creek, part of today's Fort Circle Parks.

Photo courtesy of the Library of CongressIn the 1860s, 68 forts, 93 batteries, and 20 miles of trenches were built to encircle the nation’s capital. In the immediate vicinity of Rock Creek, 16 forts occupied prominent hills including Fort DeRussey, right beside the Rock Creek valley.7 Ecobit: Ridgetop River Terrace Riddle tells an interesting story about the geology of the hilltops some forts were built on.

Map tip: To find the Civil War forts closest to Rock Creek, search for "fort" on the interactive map of Rock Creek Park and select results under Historic Sites.

War-time innovations introduced permanent changes in areas that would become Rock Creek Park. On some hillsides, the more nutrient-rich and biologically active layer of topsoil was lost in the construction of infantry trenches that protected the forts. While forests have since grown back in the remaining poor soil at Fort DeRussey and other Civil War fortifications, they are much altered from the forests that stood there before the 1860s. Perhaps equally significantly, the creation of Military Road increased the opportunity for development and commerce within and west of the Rock Creek valley, leading to more traffic through the valley.

Post-Civil War: Skyrocketing Population and Development

A couple enjoying Rock Creek's banks in the 1910s, beside a decorative dam.

A couple enjoying Rock Creek's banks in the 1910s, beside a decorative dam.

Photo courtesy of the Library of CongressDuring and after the Civil War, the population of Washington, D.C. skyrocketed, as did the need for housing. Rock Creek valley’s remaining forests south of Military Road were fortunate to survive relatively unscathed, primarily because the steep terrain made development expensive and difficult. Instead, as conditions in the capital became increasingly crowded and unhealthy, more and more people sought out the natural beauty of Rock Creek as a place for reflection and restoration. President Lincoln and many subsequent presidents sought out the forest oasis as a retreat from Capitol Hill.

1890: The Birth of Rock Creek Park

In 1890, because of public reverence for its beauty, the Rock Creek valley in the District of Columbia north of the National Zoo was officially set aside as protected land. At that time, the landscape was a mosaic of clearings and forest patches. Clearings were the result of farming, war, and fire (natural and introduced).

The Growth of Rock Creek Park

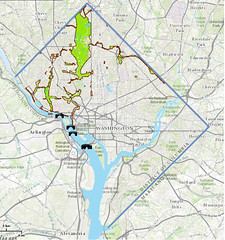

Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C., including other parcels administered by Rock Creek Park, for a total of about 2,800 acres.Since its establishment, Rock Creek Park’s jurisdiction has expanded to include the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway (lower Rock Creek—the southerly stretch between the National Zoological Park and the Potomac River), and to include tributary stream valleys that feed into Rock Creek. Other pieces of property, though not naturally connected to the Rock Creek valley, have also been added to the jurisdiction of Rock Creek Park, including the grounds of former private estates (such as Glover-Archbold Park and Dumbarton Oaks Park), historic Civil War fortifications (the Fort Circle Parks), and highly designed cultural landscapes.

Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C., including other parcels administered by Rock Creek Park, for a total of about 2,800 acres.Since its establishment, Rock Creek Park’s jurisdiction has expanded to include the Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway (lower Rock Creek—the southerly stretch between the National Zoological Park and the Potomac River), and to include tributary stream valleys that feed into Rock Creek. Other pieces of property, though not naturally connected to the Rock Creek valley, have also been added to the jurisdiction of Rock Creek Park, including the grounds of former private estates (such as Glover-Archbold Park and Dumbarton Oaks Park), historic Civil War fortifications (the Fort Circle Parks), and highly designed cultural landscapes.

The Impact Today

Well over a century since its founding, what do we see now in the landscape at Rock Creek Park? Since the abandonment of forts and fields, and the suppression of fire, the forests have returned. Today, 85 percent of Rock Creek Park is forested again.

However, in areas where the most severe or recent soil and/or vegetation disturbance occurred, Rock Creek’s forest communities are still recovering. Soils are a major predictor of the type of natural community at a site, and once the important topsoils have been lost (due to erosion, or earthmoving during the construction of earthen fortifications, for instance), the recovery of the soils and the natural communities they supported is an extremely long process—more than several hundred years in some cases. Not surprisingly, many forest communities in areas of the park known to have been cleared before or during the Civil War—especially between Military Road and Wise Road—have characteristics of semi-natural (or successional) communities. With time, natural processes may help them regain more soil microorganisms and better soil structure that help support healthy natural communities.

Ecobit: Forest Succession—Clues to the Past

Mowed picnic area along Rock Creek.

Mowed picnic area along Rock Creek.

Photographer: Erin Lunsford Jones, courtesy of NatureServeSome green areas at Rock Creek Park are designed or being maintained by landscapers. Lawns, shady mowed picnic areas, and planted areas are examples. Non-forested areas at the park nearly all fall into this category. The National Park Service maintains some areas as open meadows for wildlife, and others as places of recreation.

Map tip: To find these kinds of non-forested green areas at Rock Creek Park, go to the interactive map of Rock Creek Park and search for "open space" or "meadow."

All parts of Rock Creek Park bear the stamp of their unique land use history. Ecobit: Escaped Art

- 1. . 2016. Native Peoples of Washington, DC.

- 2. . 2007. Ecological communities of the Potomac Gorge in Virginia: composition, floristics, and environmental dynamics.

- 3. . 1995. Annotated checklist of vascular plants of Rock Creek Park, National Park Service, Washington, D.C. Castanea. 60(4):283-316

- 4. . 1990. Historic resource study.

- 5. . 2003. Rock Creek Park.

- 6. . 2009. Civil War Defenses of Washington: Natural History and Physical Setting.

- 7. . 2009. Civil War Defenses of Washington: History and Culture.